Journal of Our Meditation Retreat at Auschwitz-Birkenau

(Auschwitz I and II)

Faith Halter & Ralph Hammelbacher

June, 2010

The immediate origins of our decision to join a Buddhist meditation retreat

at the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camps lay:

| |

First, in Faith's decision about two years ago to begin confronting her terror

about the Holocaust; and

Second, in our trip eighteen months ago to London, to meet Roman and Susie

Halter, both Holocaust survivors. Roman is a cousin from the Polish branch of

Faith's family. He was the only member of his large nuclear family to survive

the war, as well as almost the only member of his extended Polish family to

survive. We discovered Roman's recently published memoir, ordered it online, saw

from the author's bio that he lives in London, found his phone number and

called, received a warm invitation to come visit -- and about a month later, we

spent five days getting to know Roman and Susie. They were so gracious and

welcoming and we were so grateful for the chance to meet them. Roman is the same

age as Faith's father. Their grandfathers were half-brothers; Faith's

great-grandfather emigrated to London in the early 1900s and the two branches of

the family gradually lost contact. |

After our return from London, Faith's friend Jill reminded her of a Buddhist

organization that leads an annual retreat at Auschwitz. Faith had forgotten all

about this; it was many years since she had told Jill about the book that

describes the first of these retreats, Bearing Witness by Bernie Glassman. Six

months after Jill's reminder, in early June, Ralph and Faith were in Poland to

participate in this yearís Bearing Witness retreat for five nights.

We decided to create this photo-journal to mark in own minds and hearts some of

the intensity of this experience, and also as a way to share with our families

and friends some small insight into our indescribable experience.

We want to acknowledge our gratitude to the Zen Peacemakers organization that

arranges these retreats. 160 people attended this year! We did not join most

group activities after the first day because we realized that we needed to carry

out our pilgrimage in private, but the group still provided a valuable structure

and support community. It also provided special access to some of the sites that

was invaluable.

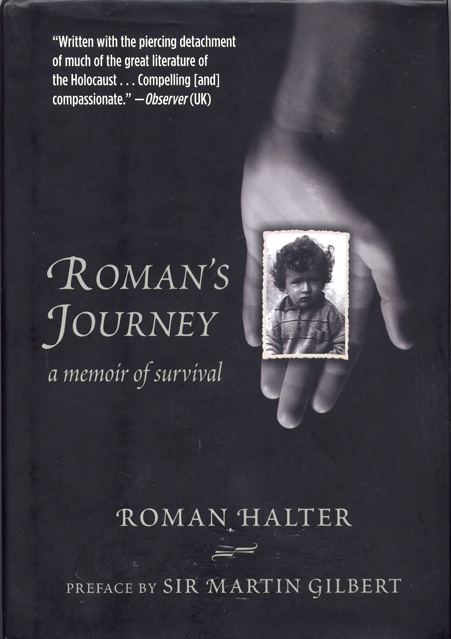

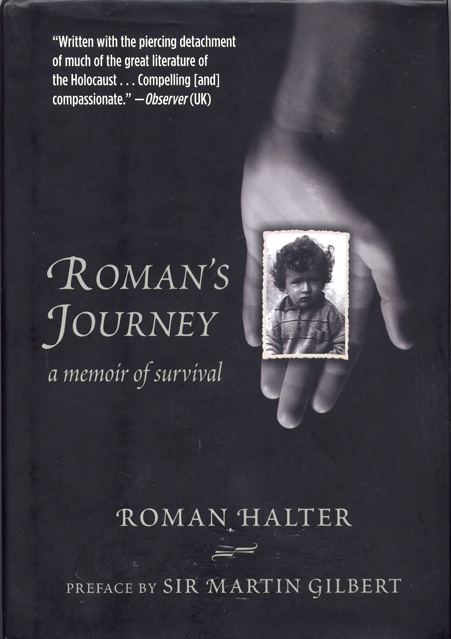

This

is the cover of Roman's memoir. We highly recommend it. It is beautifully and

clearly written and extremely moving.

This

is the cover of Roman's memoir. We highly recommend it. It is beautifully and

clearly written and extremely moving.

This

is the infamous entry gate to Auschwitz I, the first death camp built by the

Nazis, a few kilometers from the small town of Oswiecim. They chose this

location because of its proximity to multiple railway lines.

This

is the infamous entry gate to Auschwitz I, the first death camp built by the

Nazis, a few kilometers from the small town of Oswiecim. They chose this

location because of its proximity to multiple railway lines.

The words arching over the entrance are German: Arbeit Macht Frei. They mean,

"Work Will Make You Free."

The photo on the left shows how it looks today.

As

you can see from the Nazi-era image on the right, the entrance has hardly changed. Look at the man standing by

the gate on the left in the old photo; it will help you see that the entryway is not so big,

especially when you think of the countless numbers of Nazi victims who passed

through.

As

you can see from the Nazi-era image on the right, the entrance has hardly changed. Look at the man standing by

the gate on the left in the old photo; it will help you see that the entryway is not so big,

especially when you think of the countless numbers of Nazi victims who passed

through.

In this image, note the white building just behind the tree without leaves Ė

perhaps the very same tree in full leaf in our previous photo.

Here

you are looking from the opposite side of the entry road at the same white

building. In that small area beside the building, is where the Jewish prison

orchestra played marches every morning and night as the prisoners doing slave

labor had to keep time as they departed in the early morning and returned many

hours later.

Here

you are looking from the opposite side of the entry road at the same white

building. In that small area beside the building, is where the Jewish prison

orchestra played marches every morning and night as the prisoners doing slave

labor had to keep time as they departed in the early morning and returned many

hours later.

You

are looking down one of the "streets" of Auschwitz I. Notice that the buildings

are all intact. It could be a neighborhood almost anywhere, if not for the

barbed wire and the guardhouse at the end of the street.

The next few images take you closer and closer in to what it would have been

like to be living in that evil place that looks so superficially normal from a

distance.

Auschwitz is known primarily as the place where the Nazis "perfected" their

aspiration to create an efficient factory for murdering people. However, in

Auschwitz as everywhere else, they also conducted more formal executions by

other means, designed to intimidate and terrorize the slave laborers -- those who were not immediately sent to the gas chambers

upon arrival.

This photo shows the gallows that could accommodate multiple hangings.

This photo shows the gallows that could accommodate multiple hangings.

The photo to the right shows the execution wall where prisoners were lined

up and shot.

The photo to the right shows the execution wall where prisoners were lined

up and shot.

Now you are looking inside the gas chamber. If you look near the top

center, you

can faintly see the square opening in the ceiling (now covered by wood), one of

two where they dropped in the Zyklon B gas that killed by suffocation.

Now you are looking inside the gas chamber. If you look near the top

center, you

can faintly see the square opening in the ceiling (now covered by wood), one of

two where they dropped in the Zyklon B gas that killed by suffocation.

Our group had special permission to move behind the barrier. We were told that

300 people were routinely squeezed into this gas chamber. All 160 of us moved as

close together as we could into the center. This did not begin to approximate

the conditions of an actual execution, but it gave us a tiny glimpse of how it

might have felt at the onset.

A door on the left side of the gas chamber opened to the crematorium. Just a few

steps to shift the victims' bodies into the furnaces. The bodies were placed on

the metal carts on the left, which rolled on tracks (see foreground), right into

the furnaces. Faith was particularly struck by how narrow were the trays that

held the corpses. She thought about how easily they would have accommodated the

emaciated bodies of people who had already been starving for weeks, months or

years.

A door on the left side of the gas chamber opened to the crematorium. Just a few

steps to shift the victims' bodies into the furnaces. The bodies were placed on

the metal carts on the left, which rolled on tracks (see foreground), right into

the furnaces. Faith was particularly struck by how narrow were the trays that

held the corpses. She thought about how easily they would have accommodated the

emaciated bodies of people who had already been starving for weeks, months or

years.

This special gallows stands just outside the gas chamber. This is where the camp

commandant, Rudolf Hoess, was hung after the Nuremberg trials.

This special gallows stands just outside the gas chamber. This is where the camp

commandant, Rudolf Hoess, was hung after the Nuremberg trials.

This is our last photo from Auschwitz I. After the war, many of the former

barracks were "adopted" by different governments that wanted to establish small

commemorative museums. This is a room from the Belgian Government exhibit. Each

blown-up photo shows one or two people from a specific transport to the death

camp, with the dates of deportation and extermination at the top. At the bottom,

the second number from the left shows how many were in that particular

transport. The number at the far bottom right shows how many survived; in many

cases, that number is zero.

This is our last photo from Auschwitz I. After the war, many of the former

barracks were "adopted" by different governments that wanted to establish small

commemorative museums. This is a room from the Belgian Government exhibit. Each

blown-up photo shows one or two people from a specific transport to the death

camp, with the dates of deportation and extermination at the top. At the bottom,

the second number from the left shows how many were in that particular

transport. The number at the far bottom right shows how many survived; in many

cases, that number is zero.

Auschwitz I was used primarily to murder Polish political prisoners and others

victimized by the Nazis relatively early in the war. As the Nazis' mass

extermination plans exploded in magnitude, their needs quickly outgrew the

campís capacity. (You can walk from one end of the camp to the other in less

than ten minutes.)

Their solution was to build an enormous new camp about 3 kilometers away --

Auschwitz II, also called Birkenau. Birkenau was built so that a railway line

ran directly into the camp itself, conveniently depositing the cattle cars full

of victims near four large gas chambers/crematoria. Birkenau extends some 430

acres.

The track could easily accommodate a train with 35 cattle cars, the number in

the transport that carried Faith's cousin Roman and others from the liquidated

Lodz ghetto to Auschwitz.

This first photo from Birkenau shows the tracks with switching points, which

facilitated trains arriving and departing around the clock. The pathway on the

left where visitors are walking is where the cars were emptied and the

"selections" took place. This is where Dr. Mengele and his staff quickly scanned

the new arrivals who had not died en route, pointing one way for those being

sent directly to the gas chamber and another way for the relatively few deemed

sufficiently fit to serve as slave labor.

This first photo from Birkenau shows the tracks with switching points, which

facilitated trains arriving and departing around the clock. The pathway on the

left where visitors are walking is where the cars were emptied and the

"selections" took place. This is where Dr. Mengele and his staff quickly scanned

the new arrivals who had not died en route, pointing one way for those being

sent directly to the gas chamber and another way for the relatively few deemed

sufficiently fit to serve as slave labor.

Here we are looking back down the track, towards the entrance to Birkenau.

Under the watchtower is the rail entrance, and to the right is the entrance for people

and other vehicles. The train sitting on the track is a restored smaller-size car that was

used for transporting Hungarian Jews late in the war.

Here we are looking back down the track, towards the entrance to Birkenau.

Under the watchtower is the rail entrance, and to the right is the entrance for people

and other vehicles. The train sitting on the track is a restored smaller-size car that was

used for transporting Hungarian Jews late in the war.

The next two photos show chaotic scenes of victims being unloaded and lined up

for "selection." You can see the

modern-day site to the side of the display photos.

This

is a shot from the watchtower built over the rail entrance. You can see that

some barracks remain intact today. However, for most of the site, which extends

far out ahead, left and right, nothing remains of the barracks except the

chimneys.

This

is a shot from the watchtower built over the rail entrance. You can see that

some barracks remain intact today. However, for most of the site, which extends

far out ahead, left and right, nothing remains of the barracks except the

chimneys.

On

the other hand, most of the barbed wire -- which was all electrified at the time

-- is still intact. Birkenau was enormous; it was

divided into sub-camps delineated by paths lined by barbed wire and steep

V-shaped ditches, which remain. There are also steep V-shaped ditches on either

side of the rail tracks.

On

the other hand, most of the barbed wire -- which was all electrified at the time

-- is still intact. Birkenau was enormous; it was

divided into sub-camps delineated by paths lined by barbed wire and steep

V-shaped ditches, which remain. There are also steep V-shaped ditches on either

side of the rail tracks.

A peace plaza built after the war lies a short distance beyond the end of the

rail tracks. This is a memorial ceremony being conducted by an Israeli security

force that laid a wreath on behalf of the Office of the President of Israel.

A peace plaza built after the war lies a short distance beyond the end of the

rail tracks. This is a memorial ceremony being conducted by an Israeli security

force that laid a wreath on behalf of the Office of the President of Israel.

Initially there were two crematoria at Birkenau, one on each side of the end of

the tracks. These were numbers 2 and 3 (number 1 was the Auschwitz I

crematorium). The Nazis later added two more crematoria at Birkenau, for a total

of five at the Auschwitz-Birkenau camps.

As the Allied forces drew near at the end of the war, the SS blew up three of

the four crematoria at Birkenau, in a ludicrous attempt to destroy the evidence

of their war crimes. The fourth had been blown up shortly before by Jewish

prisoners, a revolt that raised spirits throughout the camp but also resulted in

severe reprisals and eventual capture and death of those who carried out the

revolt. One woman, who smuggled explosives from her job as a slave laborer, was hung before all the inmates at Auschwitz I in a scene that is

recounted in many of the books written by camp survivors.

In this image, we are looking at the remains of the steps down which prisoners

were herded into the gas chamber of Birkenau crematorium #2.

In this image, we are looking at the remains of the steps down which prisoners

were herded into the gas chamber of Birkenau crematorium #2.

Here we are looking from the back of crematorium #4, the one blown up by Jewish

prisoners, towards the "bathhouse" or "sauna." This is the building where transportees destined for slave labor were deprived of all their clothes and any

remaining belongings, disinfected, shaved, tattooed, and given ill-fitting,

flimsy striped prison garb.

Here we are looking from the back of crematorium #4, the one blown up by Jewish

prisoners, towards the "bathhouse" or "sauna." This is the building where transportees destined for slave labor were deprived of all their clothes and any

remaining belongings, disinfected, shaved, tattooed, and given ill-fitting,

flimsy striped prison garb.

Birkenau, besides being the main death camp, was also a major transit station

for moving around prisoners, especially towards the end of the war when the

Nazis began shifting concentration camp populations as the Allied forces

advanced. Some of the people who passed through the "bathhouse" ended up at

other camps. This was the experience of Roman, who spent ten days in "quarantine" at Auschwitz before being sent on to the Stutthof concentration

camp (where it was a relief to find "only" one crematorium), and then later to

slave labor in Dresden, shortly before the city was firebombed.

It was standard practice to "quarantine" new arrivals selected for slave labor.

They were confined for about two weeks to barracks run by the most sadistic

guards in the camp, for the express purpose of breaking their spirits and

indoctrinating them to obey all rules and procedures. Anyone who became sick or

otherwise broke down under the virtually constant brutality and torture was sent

to the "infirmary." Few returned from the "quarantine infirmary." Most were sent

to the gas chamber.

Just beyond the remains of crematorium #4 lie three ponds. These were ash pits

for disposal of what remained after burning the bodies of those who were gassed

or were killed by other means (hanging, shooting, beating, starvation, illness,

medical experiments, work injuries, etc.). There was also an open area nearby

for burning additional bodies at times when the crematoria were already

operating at full capacity.

This is a photo of the largest of the ponds that were formerly ash pits. Such

deceptive beauty.

This is a photo of the largest of the ponds that were formerly ash pits. Such

deceptive beauty.

This pond/ash pit is one of many, many places all around Birkenau where we said

Kaddish, the Jewish prayer of mourning for the dead. This is how we spent most

of our time at Birkenau on our own, after the first day of touring both camps

with our group.

We said Kaddish dozens and dozens of times, for family members, for friends and

their families, for all the souls known and unknown of those who suffered

persecution and, in most cases, extermination. Each time we recited Kaddish for

a specific person, we first spoke to that person as if he or she were present,

sharing whatever memories, stories or background information we had.

The Kaddish prays that "the Great Name whose Desire gave birth to the Universe .

. . [will] rule your life and your day and all lives of our World." It ends with

a wish for peace. (This quote is from the English translation used by the Zen

Peacemakers. The group also recited translations in Polish and German.)

The next three photos are of a barrack where Faith and Ralph received permission to spend the

entire night alone. This was an offshoot of the special practices and access of

the Zen Peacemakers group. During each retreat, they spend part of one evening

holding a vigil for the dead in one of the barracks. We made special arrangements

to stay by ourselves in a barrack near where the main group met.

We spent the night in one of the original barracks, which were built to hold 52

horses each. Instead, they were converted to housing for prisoners, with tiered

bunk beds crammed together. Four to eight prisoners typically shared a single

tier of each bunk, living in unimaginably horrible conditions. Sanitation was

essentially non-existent and all sorts of infestations, infections and diseases

were rampant.

Our vigil began at 7:00 p.m. We sat behind the barracks while the sun set and

there was still enough light to read. We took turns reading from the section of

Romanís book that describes his experiences from the time when the Nazis

liquidated the ghetto in Lodz, Poland where he, his parents, grandfather and a

few other family members lived in dire circumstances for years, up through the time when he was imprisoned

at Auschwitz. Roman's father, grandfather and nephew died in the ghetto. His

remaining close family members were subsequently murdered in concentration

camps.

As it became dark, we moved inside. We sat for a long time, feeling the energy

of the space and waiting for it to become more quiet as the majority of our

group left in two shifts, at 9:00 and midnight.

It was pitch black inside. As we focused on the space, we both began to feel

more strongly the evil of this terrible place, and the unimaginable suffering

that happened there over several years. We discussed whether we were simply

projecting onto our experience what we already knew, but both of us felt

strongly that our feelings were real.

This was confirmed when we reached beyond the chains cutting off access to the

main part of the barrack and touched the three-tiered bunk beds. The feelings of

awfulness became incredibly magnified, more than words can explain. It was

terrifying, especially for Faith, who felt as if she really were a prisoner in

the camp. This sense was intensified by the constant coming and going of nearby

trains all through the night, with us imagining that each one was bringing another

transport.

It felt like we were truly in Hell. We followed our meditation practices of

following our breath, tracing sensations in our bodies, feeling the ground

beneath us, doing our best to stay present to our experience and being a support

to each other (mostly Ralph supporting Faith, who was feeling much more intense

fear and anguish). We spent much of the time sitting with our backs to the side

of the chimney that you can see in the front of the interior.

After many hours, Faith began to feel a different kind of energy, coming from a

bunk bed farther down the row beyond the chains. It carried a clear sense of

determination, courage and calm. Someone passed through this awful place whose

energy was so strong, powerful and positive that it left a mark that was clearly

perceptible to her. This was a great comfort to both of us. It helped us to sit

with calmer, more open hearts for the remaining hours till dawn.

As it slowly became light, we recited Kaddish and also Buddhist prayers for the

souls of all who suffered, starting from the barrack where we were, and

spreading out into larger and larger rings. After the sun was fully up, we read

together some passages from Romanís book about his will to live, and also his

beloved grandfatherís favorite prayer.

This last photo of the track shows where we ended our visit to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

The shadow is because we were sitting where the track first enters Birkenau,

beneath the main guardhouse. We said our final Kaddishes here. Then, as we left

the camp, we stood at the entrance facing outward, and recited one last Kaddish

and Buddhist prayer for all people through all time who have suffered from war

and brutality, along with our wishes for peace.

This last photo of the track shows where we ended our visit to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

The shadow is because we were sitting where the track first enters Birkenau,

beneath the main guardhouse. We said our final Kaddishes here. Then, as we left

the camp, we stood at the entrance facing outward, and recited one last Kaddish

and Buddhist prayer for all people through all time who have suffered from war

and brutality, along with our wishes for peace.

Back in Krakow, which is about 35 miles from Auschwitz-Birkenau, we took a

couple of days to reflect on our experience and visit places important to local

Jewish history.

This is the first synagogue of seven that were built in the Jewish district of

Krakow, the Kazimierz. Notice that it was built below ground level. That was

partly in obedience to a law requiring that no Jewish building be as high as any

church and also to avoid appearing in any way ostentatious to the non-Jewish

population. The original building (right side) was constructed in the early 15th

century.

This is the first synagogue of seven that were built in the Jewish district of

Krakow, the Kazimierz. Notice that it was built below ground level. That was

partly in obedience to a law requiring that no Jewish building be as high as any

church and also to avoid appearing in any way ostentatious to the non-Jewish

population. The original building (right side) was constructed in the early 15th

century.

This is the

Izaak Jakubowicz Synagogue. Its members were too poor to own Siddurs (prayer books)

and so the major Hebrew prayers were painted on its walls. The Nazis painted

over the prayers when they converted the synagogue to other uses, but part of

the underlying script has been restored. There is a contemporary Siddur in the

foreground of the photo.

This is the

Izaak Jakubowicz Synagogue. Its members were too poor to own Siddurs (prayer books)

and so the major Hebrew prayers were painted on its walls. The Nazis painted

over the prayers when they converted the synagogue to other uses, but part of

the underlying script has been restored. There is a contemporary Siddur in the

foreground of the photo.

Here is

the 16th-century "New" Synagogue, one of a few private synagogues, built by a wealthy family. The Nazis

stripped all of Krakow's synagogues of their original furnishings and they have

been refurbished with materials from synagogues in outlying districts. However,

the Nazis did not bother to destroy stonework, and so the carved ark in the

background is original, with the decoration restored after the war.

Here is

the 16th-century "New" Synagogue, one of a few private synagogues, built by a wealthy family. The Nazis

stripped all of Krakow's synagogues of their original furnishings and they have

been refurbished with materials from synagogues in outlying districts. However,

the Nazis did not bother to destroy stonework, and so the carved ark in the

background is original, with the decoration restored after the war.

Much of the restoration of the Kazimierz District occurred after the film

Schindlerís List was released. Part of it was filmed here. The film generated a

massive rejuvenation. Kazimierz is now a major tourist destination, with

original buildings that have been carefully renovated, restaurants that sell

Jewish-style food, and a

Jewish bookstore (called Jarden) that organizes tours.

The Schindler factory is located a short walk from the Kazimierz, on the other

side of the Wisla River. It has been converted to a museum that documents the

Nazi occupation of Krakow. This is a photo of Schindlerís desk.

The Schindler factory is located a short walk from the Kazimierz, on the other

side of the Wisla River. It has been converted to a museum that documents the

Nazi occupation of Krakow. This is a photo of Schindlerís desk.

As one passes through the museum exhibits, they gradually turn to the plight of

Krakowís Jewish population as the Nazis herded them into a ghetto adjacent to

the main railway station. The Nazis took great pains to design the ghetto in

ways that would promote at every level a sense of hopelessness and despair. For

example, the walls were shaped to resemble headstones and also to mock the shape

of the tablets of the Ten Commandments. This is a photo of the only fragment of

the ghetto wall that remains; it was necessary to remove the walls in order to

restore the area to livability after the war.

As one passes through the museum exhibits, they gradually turn to the plight of

Krakowís Jewish population as the Nazis herded them into a ghetto adjacent to

the main railway station. The Nazis took great pains to design the ghetto in

ways that would promote at every level a sense of hopelessness and despair. For

example, the walls were shaped to resemble headstones and also to mock the shape

of the tablets of the Ten Commandments. This is a photo of the only fragment of

the ghetto wall that remains; it was necessary to remove the walls in order to

restore the area to livability after the war.

This next photo shows the square where the early deportations from the ghetto to

concentration camps occurred. The chairs are a memorial, reminders of all that

was stolen from the Jewish population, including their lives and their culture.

The ghetto was only a few square blocks in size. At the peak of overcrowding,

approximately 16,000 people were crammed into only 320 buildings including those that appear behind the plaza.

This next photo shows the square where the early deportations from the ghetto to

concentration camps occurred. The chairs are a memorial, reminders of all that

was stolen from the Jewish population, including their lives and their culture.

The ghetto was only a few square blocks in size. At the peak of overcrowding,

approximately 16,000 people were crammed into only 320 buildings including those that appear behind the plaza.

Another Nazi ploy to demoralize the Jews was to break up headstones from the

Jewish cemeteries and use them for street paving. The Jews who went outside the

ghetto for slave labor walked each day over these broken tombstone fragments; this

appears in a scene in Schindlerís List.

Another Nazi ploy to demoralize the Jews was to break up headstones from the

Jewish cemeteries and use them for street paving. The Jews who went outside the

ghetto for slave labor walked each day over these broken tombstone fragments; this

appears in a scene in Schindlerís List.

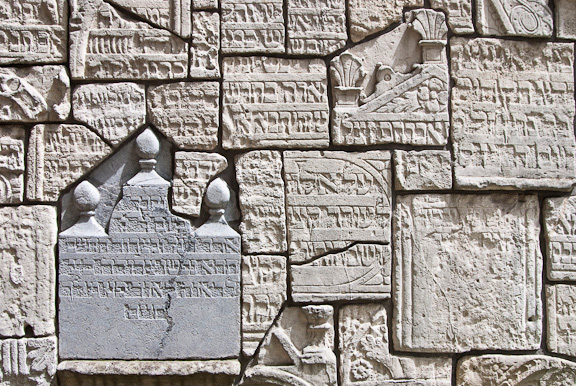

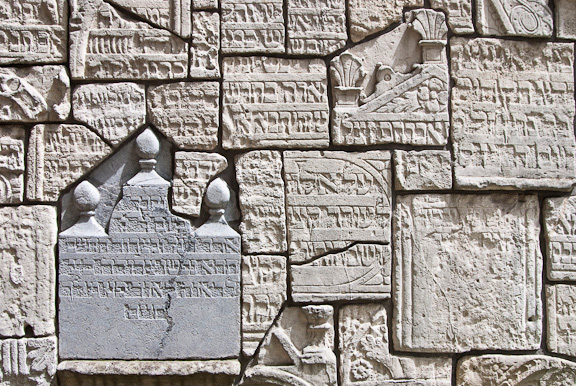

After the war, these desecrations were pried off the streets and the broken

tombstones were used to rebuild the interior walls of the old cemetery in

Kazimierz. You can see a small section of reconstructed cemetery wall in this

photo. This wall is sometimes referred to as the "Wailing Wall," reminiscent of

the Western ("Wailing") Wall in Jerusalem. As in Jerusalem, religious

supplicants write prayers and requests on small pieces of paper and leave them

in crevices.

We chose to end our visit and this photo-journal on a positive note. This photo

shows Faith with Lucyna ("Lucy") Les, owner of the Jewish bookstore (Jarden),

standing together outside the Krakow City Archives.

We chose to end our visit and this photo-journal on a positive note. This photo

shows Faith with Lucyna ("Lucy") Les, owner of the Jewish bookstore (Jarden),

standing together outside the Krakow City Archives.

At the beginning of our trip, we had gone to the bookstore to inquire about

obtaining archival information. This was because Faithís friend David had asked

her to see if she could get any information about his great-grandfather for whom

he is named. David only knew that his great-grandfather was in Krakow during

World War II.

Lucy immediately offered to accompany us to the Archives, since no one there

speaks much English. Moreover, she did extensive computer research while we were

at Auschwitz-Birkenau to track down information about Davidís family.

We went to the archives well-prepared and triumphantly emerged two hours later

with a receipt confirming that Faith would shortly receive a CD with copies of

all the documents we requested from the Krakow city census of 1900 and 1921, and

the Nazi records from the ghetto -- including David's great-grandfather's

identity card with his photograph.

Our last photo is a poster for Krakowís 19th Jewish Culture Festival, which took

place in July 2009. (We liked the poster better than the one for this yearís

20th festival.)

Our last photo is a poster for Krakowís 19th Jewish Culture Festival, which took

place in July 2009. (We liked the poster better than the one for this yearís

20th festival.)

One of the remarkable aspects about the resurgence of interest in Jewish culture

in Krakow is that it rests almost entirely on the efforts of Gentiles, mostly

Roman Catholics Ė including Lucy. There are virtually no younger Jews in Krakow.

The only ones who have not emigrated are Holocaust survivors and some of their

children.

Nevertheless, there is a vibrant, genuine interest and love for Jewish culture

and knowledge, as evidenced by activities like the Jewish Culture Festival and

Jewish Studies programs in local universities. In fact, our delightful tour

guide in Krakow, Paulina Fiejdasz, is a filmmaker who specializes in Jewish

topics.

This is the end of our photo-journal but of course, it is not the end of our

experience. We created this less than a week after our return to help us begin

to make sense of our thoughts and feelings while they were still raw and fresh.

Also, we hope that this will convey to you, our family and friends, at least a

small glimpse of what that experience was like.

No amount of reading, or watching movies and documentaries, or talking with

Holocaust survivors, or anything else, could prepare one adequately for the

reality we encountered. You cannot understand the enormous scale of Auschwitz-Birkenau

unless you see it. You canít fully grasp (not that we could, even being there)

how horrifically and efficiently they operated as factories for murdering

millions of innocent people. You canít really feel the evil and the suffering

without walking the ground where it occurred.

It was a wrenching, horrible, exhausting and yet very rewarding trip. For Faith,

it was an incredible chance to squarely face her deepest fears. For Ralph, it

made vivid the many allusions and stories he heard, growing up with parents and

grandparents who barely escaped with their lives from Germany after

Kristallnacht.

We are both so grateful for having had the opportunity to do this and do it

together. Our connection to Faith's cousins, Roman and Susie, amplified both the pain and the

fullness of our experience.

Thank you for taking the time and effort to read this.

This

is the cover of Roman's memoir. We highly recommend it. It is beautifully and

clearly written and extremely moving.

This

is the cover of Roman's memoir. We highly recommend it. It is beautifully and

clearly written and extremely moving.